Mutharasan Corridor of Migration – Finding Tamil Ancestry through Genetics in India and Beyond

We recently attended a talk hosted by RMRL, where Raj Mutharasan Sir delved into the genetic insights of Indian and Tamil ancestry. In this post, I have summarized key points from his speech

Professor Raj Mutharasan is a distinguished researcher and educator in the field of chemical and biochemical engineering. He earned his bachelor’s degree from IIT Madras, India, and his Ph.D. from Drexel University in 1973. Over his illustrious career, he has guided 30 Ph.D. dissertations and over 40 Master’s theses, significantly contributing to advancements in process control, biochemical engineering, biosensors, and related fields.

His pioneering work in biosensors has led to 12 patents, particularly in DNA, cancer biomarkers, and pathogen detection. He has received funding from prestigious agencies such as the National Science Foundation (NSF), the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). He has also served as a program director at the NSF in Washington, D.C., and as an interim dean at Drexel’s College of Engineering.

Professor Mutharasan has received numerous accolades, including the Distinguished Alumni Award from IIT Madras and Drexel University’s Research Award. His expertise has been sought by organizations like Alcoa, SmithKline Beecham, and the United Nations Development Program (UNDP).

In addition to his scientific contributions, he has a keen interest in genetics and ancestry research, closely following the field for over two decades. His recent lecture explored Indian and Tamil ancestry through genetics, shedding light on historical migration patterns and genetic lineage.

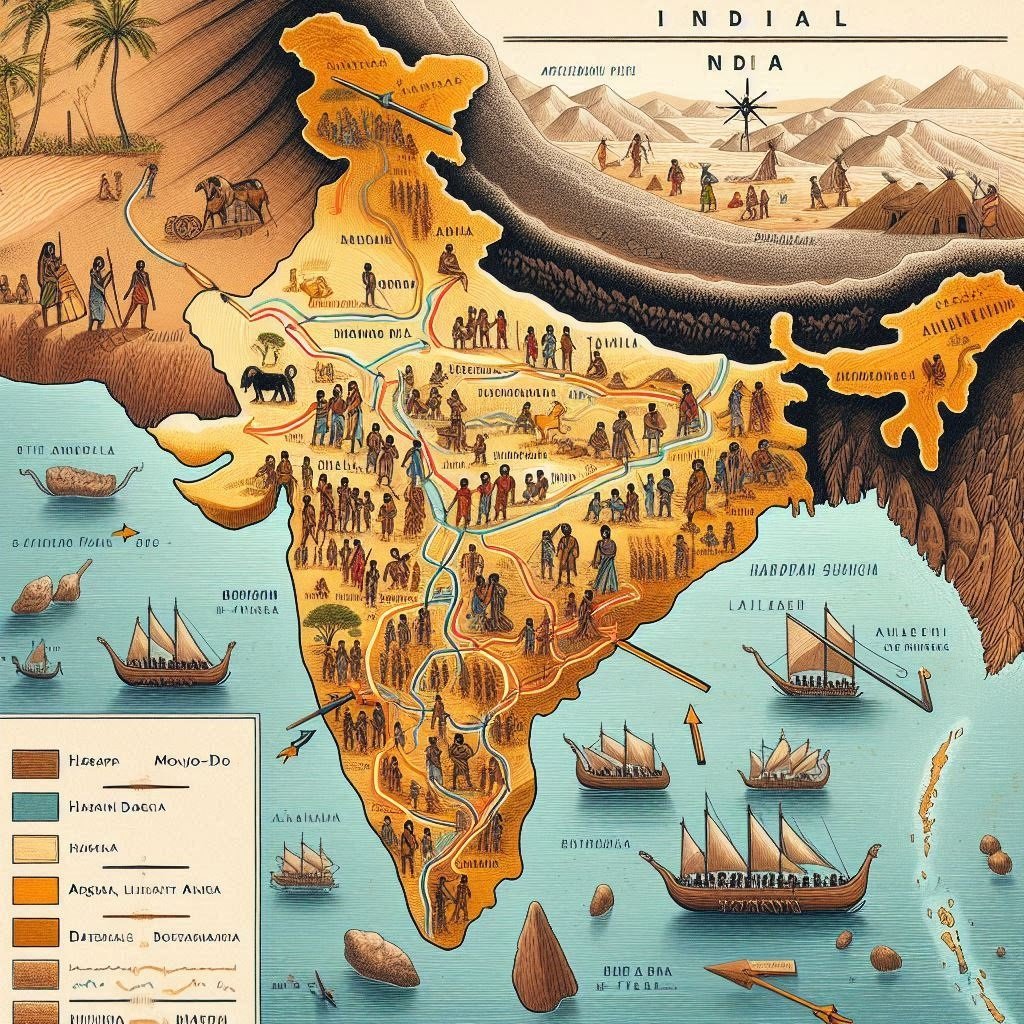

Understanding ancestry through genetics has emerged as a crucial area of study, providing new insights into human migration, ancient civilizations, and historical population shifts. Professor Raj Mutharasan, shared his insights on this fascinating field in a lecture organized under the Indus Research Center as part of the Professor M. Ananda Krishnan Endowed Lecture Series. This article delves into the key points discussed in his talk, highlighting recent genetic research and its insights into Indian and Tamil ancestry.

Background of Genetic Research is the study of ancestry using genetics gained prominence in the mid-1990s with initiatives such as the National Geographic Out of Africa Program. This project, led by geneticist Spencer Wells, funded numerous studies on human migration patterns. Indian researchers, such as Professor P.P. Majumder, also contributed significantly to this field. Over the past decade, advancements in genetic sequencing have revolutionized our understanding of human history, allowing researchers to analyze ancient DNA samples from archaeological sites worldwide.

There are Key Genetic Markers for Our Ancestry where Genetic ancestry is traced using specific markers present in human Chromosomal DNA

Y-Chromosome DNA (Paternal Lineage): Passed from father to son, the Y chromosome changes slowly over generations, making it a reliable tool for tracing male ancestry.

Mitochondrial DNA (Maternal Lineage): Inherited from the mother, mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) undergoes more frequent mutations, providing a detailed map of maternal lineage.

Whole-Genome Analysis: Though more complex and expensive, studying the entire genome helps understand population-level connections and genetic diversity.

The combination of these markers allows researchers to reconstruct historical migration patterns and relationships among various population groups.

Ancient DNA Studies and have Their own Challenges extractiig genomic material from age-old bones, The field of ancient DNA research has grown significantly since 2017, with over 10,000 ancient genomes sequenced globally. However, India lags behind with only one partially sequenced ancient genome from Rakhigarhi, a site associated with the Indus Valley Civilization. The hot and humid climate in India, which deteriorates DNA over time, , has made it difficult to obtain quality DNA material from ancient human residues. Perhaps, new techniques may be needed to deal with conditions in India. Limited investment in genetic research compared to Western countries, may have contributed to this short fall. Bureaucratic and policy restrictions on excavating and studying ancient remains are also possible contributors.

Despite these challenges, ongoing efforts at institutions like The Centre for Cellular and Molecular Biology (CCMB) Hyderabad aBirbal Sahni Institute of Palaeosciences (BSIP) in Lucknow, and Madurai Kamaraj University are making good effort in this area

These are the Major Findings on Indian Ancestry

1. Out of Africa and Early Indian Migration

Genetic evidence suggests that modern humans migrated from Africa approximately 70,000 years ago. The first groups arrived in India via coastal routes and settled across the subcontinent. Haplogroup C is one of the earliest genetic markers found in South India and is also present among Australian Aboriginal populations, supporting theories of an early coastal migration.

2. The Role of the Indus Valley Civilization

The Rakhigarhi genome study, conducted by Indian and international researchers, revealed that the Indus Valley inhabitants had a mix of ancestry related to ancient Iranian hunter-gatherers and Andamanese Tribal populations. This genetic evidence negated earlier working hypothesis that Indus Valley was settled initially by Iranian farmers. Instead, the data suggested that agricultural practices in India may have been developed independently.

3. The Spread of Indo-European and Dravidian Languages

T

The arrival of Indo-Aryan-speaking groups into India after 2000 BCE has been a topic of much debate. Genetic evidence now supports that these migrants came from Eastern Europe through Central Asia and the Steppes, entering India via the Hindu Kush mountains. They did not come via the Iranian plateau. They were the carriers of the R1a Y- haplogroup, which is now common among North Indian populations.

Conversely, South Indian Dravidian-speaking populations show higher frequencies of haplogroups such as F, R2, L and H; of these F, R2 and H are native to India, and L is related to Iranian farmers. This suggests that Dravidian languages may have been spoken across a larger region before Indo-Aryan migrations.

4. Tamil Ancestry and Genetic Markers

Recent studies have examined Tamil ancestry in depth, the L haplogroup, particularly L-M20 and L-M27, is present in reasonable proportions among Tamil populations and may have been present in Indus Valley communities. The M mitochondrial haplogroup and its subclades are widespread in South India, indicating a strong continuity of maternal lineage from ancient times. Genetic studies on tribal groups in Tamil Nadu and South India show a deep-rooted indigenous ancestry with minimal external influence.

These findings challenge long-standing narratives about population replacements and instead suggest a complex history of migration, admixture, and linguistic evolution. Genetics and Historical Migration provide data of migration. Genetic research has also provided evidence of ancient trade and migration between India and Mesopotamia. Presence of Y Haplogroup J2 among tribals in Gujarat indicates trade connections with the middle east; similar is the sitution with costal Kerala. Studies of Mesopotamian skeletons have identified mitochondrial DNA markers that match those found in India, suggesting early cultural and commercial exchanges. Similarly, genetic links between Indian and Andamanese populations indicate that the Andamanese people represent one of the oldest continuous and isolated human populations outside Africa. This further solidifies the idea of South Asia as a critical region in early human migration.

There are Challenges as well as Research opportunity in Future in the genetic field in India. Despite the groundbreaking discoveries in genetic ancestry research, several challenges remain, There is a Need for

More Ancient DNA Samples:

More excavations and studies are required to build a clearer picture of India’s past. A large collection of human remains have been collected at various excavation sites, and most of them remain unexamined for genetic residues.

Bias in Sampling Methods: Most studies in India rely on caste- or region-based sampling rather than random sampling, leading to skewed interpretations.

Interdisciplinary Approaches: Combining genetic research with archaeology, linguistics, and anthropology will provide a more holistic understanding of Indian history.

The Indian government and scientific community must invest in large-scale genetic research projects to uncover more details about the country’s rich and diverse ancestry.

To validate his finds, Professor Raj Mutharasan conducted his own genetic testing through services like 23andMe, which confirmed genetic ties to various Indian populations. Through his testing he found that he has DNA Relatives from Pakistan, Gujarat, Maharashtra, and Tamil Nadu, which appear to indicate his ancestral migratory path from Indus Valley to Tamil Nadu . He shared ancestry with populations in Fiji and Trinidad, highlights the impact of historical migrations induced by the Biritsh.

These findings demonstrate the reliability of genetic testing in tracing individual and collective ancestry.

In the end, Genetic research has revolutionized our understanding of Indian and Tamil ancestry, providing concrete evidence for historical migrations, ancient civilizations, and linguistic evolution. While challenges remain, continued advancements in DNA analysis will undoubtedly shed more light on India’s deep and complex past. As more data becomes available, we can expect an even clearer picture of how various communities within India are interconnected through centuries of migration and cultural exchange.

The study of genetics is not just about the past; it is a key to understanding identity, heritage, and the shared human story. Investing in this field will open new doors for historical and scientific exploration in India and beyond.

First Indians and Andaman Nicobar Island People

Professor Raj Mutharasan discussed how early Indians share a deep genetic connection with the tribal populations of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, particularly the Onge, Jarwa, and Great Andamanese tribes. These indigenous groups have been largely isolated for thousands of years and carry genetic markers that are closely related to South Asian hunter-gatherers, who were among the earliest settlers of the Indian subcontinent. Genetic characterization by Dr. K. Thangaraj of CCMB show that the Andamanese people belong to mitochondrial haplogroup M, which is also dominant in South Indian Dravidian populations, indicating a shared ancestry dating back to the first wave of human migration from Africa around 70,000 years ago. He emphasized that while modern mainland Indian populations have undergone genetic mixing due to later migrations, the Andamanese tribes remain a genetic time capsule, preserving the ancestry of some of the earliest Indians. This connection reinforces the theory that South Asia, including regions like Tamil Nadu, was one of the first major settlement zones for early humans before they migrated further into Southeast Asia and beyond.

Dravidian and Tamil Ancestry

In his lecture, Professor Raj Mutharasan discussed Dravidian ancestry and its significance in understanding the genetic makeup of Tamil Nadu’s current population. His insights were based on genetic studies, ancient DNA research, and migration patterns derived from Y-chromosome and mitochondrial DNA analysis. Below are the key points he highlighted regarding Dravidian ancestry and their present-day genetic footprint in Tamil Nadu.

Origins of Dravidian Ancestry

The genetic markers associated with Dravidian ancestry are primarily linked to haplogroups F, L, H. and R2. Haplogroup L, particularly the subclade L-M20 and L-M27, has been found in South Indian populations, including Tamil Nadu. Ancient Gnomic data suggests that Dravidian-speaking populations predate the migration of Indo-Aryans into the Indian subcontinent. It appears that the genetic lineage of Dravidians may have connections to ancient Iranian hunter-gatherers rather than Iranian farmers, as previously believed. The Indus Valley Civilization (IVC) people may have shared genetics with Dravidian-speaking populations, indicating a possible connection between the Indus Valley Civilization and Dravidian ancestry.

Dravidian Genetic Markers in Tamil Nadu

Mitochondrial DNA analysis shows that haplogroup M is predominant in Tamil Nadu, found in both tribal and caste populations.

This suggests that the maternal lineage of Tamils has remained largely continuous over thousands of years. The L haplogroup, which has been traced to the Indus Valley Civilization, is also found among South Indian populations, supporting theories of early Dravidian presence in the region. Genetic studies on tribal communities in Tamil Nadu indicate that they share many ancestral markers with early South Asian populations, reinforcing their indigenous status.

Influence of Indo-Aryan Migrations on Tamil Nadu’s Population

The Indo-Aryan migrations, primarily associated with haplogroup R1a, had minimal impact on South India compared to North India. Genetic evidence shows that the Dravidian-speaking populations in Tamil Nadu have maintained distinct genetic characteristics despite cultural and linguistic influences from Indo-Aryan groups. While R1a is present in Tamil Nadu, it is significantly lower than in North India, indicating that Indo-Aryan ancestry was limited.

The Blended Nature of Tamil Nadu’s Population

Professor Mutharasan emphasized that there is no “pure” Tamil or Dravidian ancestry, as genetic studies indicate that all human populations are mixed over time. The genetic diversity in Tamil Nadu results from continuous interactions between various populations over thousands of years. Even though Dravidian genetic markers dominate, minor genetic influences from Indo-Aryan and other migrations have contributed to Tamil Nadu’s current population structure.

Tamil Nadu’s Genetic Continuity and Cultural Identity

Despite migration and admixture, the Dravidian genetic heritage remains strong in Tamil Nadu. The persistence of haplogroups F, H, L, and R2 in both caste and tribal populations indicates that the Dravidian ancestry has not been significantly diluted over time. The study of genetics helps in understanding historical migrations, cultural exchanges, and linguistic evolution in Tamil Nadu.

Professor Raj Mutharasan’s analysis of Dravidian ancestry in Tamil Nadu highlights the deep-rooted genetic heritage of the Tamil population. While the region has seen interactions with various groups over millennia, the core Dravidian genetic markers remain dominant, particularly in maternal lineage (mtDNA M haplogroup) and paternal lineage (Y-chromosome haplogroups L and H). The findings challenge past theories that Indo-Aryans played a major role in shaping South Indian populations and instead suggest a long-standing, largely uninterrupted Dravidian lineage in Tamil Nadu.

Are Tamils and Dravidians being Same?

Dravidian Ancestry and Its Genetic Origins

Dravidian ancestry predates Indo-Aryan migration and has deep genetic roots in the Indian subcontinent. The Dravidian-speaking populations are associated with specific genetic haplogroups, mainlyHaplogroup L (L-M20, L-M27) and Haplogroup H (found predominantly in South India), Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroup M (strong maternal lineage continuity in Tamil Nadu).

Genetic studies show strong connections between Dravidians and the Indus Valley Civilization (IVC), indicating that the civilization’s inhabitants were genetically related to modern South Indian populations. The early inhabitants of the Indian subcontinent, including hunter-gatherers and early agriculturists, contributed significantly to the Dravidian gene pool.

Tamil People and Their Genetic Identity

Tamils, as a subset of the Dravidian population, share ancient genetic markers that have been relatively stable over thousands of years. Tamil ancestry can be traced back to prehistoric migrations from Africa (about 70,000 years ago) and later genetic mixing within South Asia. The genetic composition of Tamil Nadu includes markers from ancient South Asian indigenous groups, Indus Valley inhabitants, and minor influences from Indo-Aryan migrations. Unlike North Indian populations, Tamil Nadu has retained a stronger Dravidian genetic signature due to limited influence from later Indo-Aryan migrations.

The Impact of Indo-Aryan Migrations on Tamil Nadu

While North India experienced a strong genetic influx from Indo-Aryan groups (haplogroup R1a), Tamil Nadu remained relatively unaffected by large-scale Indo-Aryan settlement. Some Indo-Aryan genetic markers are present in Tamil Nadu, but they constitute a small fraction of the overall genetic makeup. Genetic data shows that the Dravidian language and culture existed long before Indo-Aryan influence spread across India. Tamil people have preserved linguistic, cultural, and genetic continuity despite historical interactions with other groups.

The Blended Nature of Tamil Nadu’s Population

Professor Mutharasan emphasized that no population is “pure”, as all human groups have undergone migrations and genetic admixtures over time. Tamil Nadu’s genetic diversity reflects a mixture of ancient indigenous groups and smaller external influences. The Dravidian genetic heritage dominates, but the population includes minor traces of migrations from Central Asia, Persia, and even Mesopotamia due to ancient trade routes. Despite this, Tamil people have retained a distinct genetic and cultural identity, shaped by a continuous historical presence in South India.

Tamil People and the Indus Valley Connection

The Indus Valley Civilization (IVC) people shared genetic similarities with Dravidian-speaking populations. The Rakhigarhi DNA study (Indus Valley site) revealed that the people of the IVC were related to ancient Iranian hunter-gatherers, not Iranian farmers, as previously thought. Linguistic studies suggest that the IVC people may have spoken a proto-Dravidian language, strengthening the link between Tamils and the Indus Valley Civilization.

Tamil Genetic Continuity and Maternal Lineage

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) haplogroup M is highly prevalent in Tamil Nadu, indicating maternal lineage continuity from ancient times. Even among tribal groups and different caste groups, the genetic markers show a strong connection to early South Asian populations. The paternal lineage (Y-chromosome) also supports the Dravidian connection, with haplogroups L and H being predominant in Tamil Nadu.

Genetic Studies on Tamil Tribes and Caste Populations

Studies on Tamil tribal groups, such as the Kurumans and Irulas, show deep ancestral links to early South Asian populations. Even within different caste communities, the genetic variations are minimal, reinforcing the idea that the entire Tamil population shares a common ancestry. Tamil Brahmins, despite some Indo-Aryan influences, still carry strong Dravidian genetic markers, indicating long-term integration into the Tamil population.

Tamil Identity Beyond Genetics

Professor Mutharasan pointed out that language and genetics are not always connected. Genetic ancestry does not determine cultural or linguistic identity; for example, people with similar genetics may speak different languages due to historical migration and cultural shifts. The Tamil language and culture have been resilient, preserving Dravidian heritage despite influences from Indo-Aryan and colonial histories.

Professor Raj Mutharasan’s talk provided compelling genetic evidence that Tamil people are deeply connected to the ancient Dravidian lineage, with strong continuity from prehistoric times. While there has been some genetic blending over the millennia, Tamil Nadu remains one of the strongest representations of Dravidian ancestry in India.

His lecture emphasized that genetics, archaeology, and linguistics together reveal a rich, complex history of Tamil people, showcasing their indigenous roots, cultural evolution, and remarkable genetic continuity over thousands of years.

Professor Raj Mutharasan’s Insights on Aryan Migration and Its Relation to Indian and Tamil Populations

In his lecture, Professor Raj Mutharasan addressed the topic of Aryan migration and its impact on Indian and Tamil populations based on genetic research and ancient DNA studies. His discussion focused on the movement of Indo-Aryans, genetic markers associated with the migration, and how this affected South India and Tamil Nadu.

The Aryan Migration Theory and Its Genetic Evidence

The Aryan Migration Theory (AMT) suggests that Indo-Aryans entered India around 2000 BCE from Central Asia, passing through the Hindu Kush mountains into the Indus Valley region and later spreading into northern and central India. Genetic research has provided strong evidence supporting this migration, particularly with the identification of haplogroup R1a in North Indian populations. The Yamnaya culture from Eastern Europe and Central Asia has been linked to the Indo-Aryan expansion, with linguistic and genetic evidence pointing toward their influence in India. The genetic data contradicts earlier Aryan Invasion theories (AIT), which suggested a violent takeover. Instead, the migration was likely gradual, involving cultural exchanges and mixing with existing populations.

How Aryan Migration Affected Indian Populations

The Indo-Aryans mixed with the native populations, leading to a genetic blend of early South Asians (Dravidians) and incoming Indo-Europeans. North Indian populations show a significant presence of R1a haplogroup, which is almost absent in South India, indicating that the Indo-Aryan migration had limited influence on Tamil Nadu and other Dravidian regions. Indo-Aryan influence shaped North Indian languages (Sanskrit-based), religious practices (Vedic traditions), and social structures (varna/caste system). However, the Dravidian-speaking regions, including Tamil Nadu, retained their linguistic and cultural distinctiveness despite limited genetic interaction.

Indo-Aryan Influence in Tamil Nadu and South India

Unlike North India, Tamil Nadu remained largely unaffected by large-scale Indo-Aryan migration. While some R1a presence exists in South India, it is significantly lower than in North India, meaning that the genetic impact of Indo-Aryans on Tamil Nadu was minimal. Tamil Nadu’s population primarily carries Dravidian genetic markers, such as:

- Y-chromosome haplogroups L, H, and R2 (Native South Asian)

- Mitochondrial haplogroup M (Maternal lineage)

The limited Indo-Aryan genetic presence in Tamil Nadu suggests that while there were cultural exchanges, South India retained its indigenous Dravidian ancestry.

Differences Between North Indian and Tamil Genetic Populations

North Indians have a higher proportion of Indo-Aryan genetic markers, especially R1a haplogroup, which is associated with steppe pastoralists from Central Asia. South Indians, including Tamils, carry more indigenous genetic markers, particularly those linked to the Indus Valley Civilization and pre-Indus hunter-gatherers. Genetic studies have confirmed that Dravidian languages were spoken in a larger region before Indo-Aryan expansion, meaning that North India was originally Dravidian-speaking before Sanskrit and Indo-Aryan languages spread. Despite linguistic and cultural exchanges, the Tamil population has retained a strong genetic continuity, showing little intermixing with Indo-Aryan groups.

Tamil-Dravidian Connection to the Indus Valley Civilization

The Indus Valley Civilization (IVC) was one of the most advanced ancient civilizations, and genetic evidence suggests a strong connection between its people and modern Dravidian-speaking populations. The Rakhigarhi DNA study, which analyzed an Indus Valley skeleton, showed that the individual had no genetic links to Indo-Aryans but instead was related to ancient South Asian and Iranian hunter-gatherers. This reinforces the theory that Dravidian people were the original inhabitants of the Indian subcontinent and that the Indus Valley people may have spoken a proto-Dravidian language.

Key Takeaways from Raj Mutharasan’s Talk on Aryan Migration and Tamil Population

- Aryan migration occurred around 2000 BCE but had little genetic impact on Tamil Nadu.

- Indo-Aryans mixed significantly with North Indian populations but not with South Indians.

- Tamil people retain a predominantly Dravidian genetic heritage, with limited R1a presence.

- The Indus Valley Civilization is likely connected to Dravidian ancestry, not Indo-Aryans.

- Genetics supports the idea that Dravidian-speaking people occupied a larger region before Indo-Aryan expansion.

- Language and genetics are not directly related—while Indo-Aryan languages spread through cultural dominance, the genetic composition of South Indians remained largely Dravidian.

Professor Raj Mutharasan’s discussion on Aryan migration and Tamil ancestry revealed that while Indo-Aryans influenced North India, their genetic and cultural impact on Tamil Nadu and Dravidian populations was minimal. Tamil populations have maintained a strong genetic continuity, with deep-rooted connections to the Indus Valley Civilization and pre-historic South Asian hunter-gatherers. His lecture reinforced the idea that Tamil and Dravidian ancestry is ancient and indigenous, predating Indo-Aryan migrations and highlighting the genetic and cultural distinctiveness of South India.

Haplogroup U

In his lecture, Professor Raj Mutharasan discussed Haplogroup U, particularly its presence in India and Tamil Nadu, its origins, and its significance in tracing maternal ancestry. Haplogroup U is a mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) haplogroup, meaning it is inherited exclusively from the mother, making it a key marker for studying maternal lineage. Below is a detailed explanation of what he said about Haplogroup U and its connection to Indian and Tamil populations.

Origins of Haplogroup U

Haplogroup U is an ancient mitochondrial haplogroup that originated around 55,000 to 60,000 years ago. It is widely distributed across Eurasia, South Asia, and North Africa. Haplogroup U is found in both European and South Asian populations, but subclades of U differ by region.

Haplogroup U in India and Tamil Nadu

Haplogroup U is one of the dominant maternal haplogroups in India and is found in both Indo-Aryan and Dravidian populations. The U subclades found in India (such as U2, U7, and U8) are distinct from those found in Europe (such as U5), indicating that Indian U lineages have deep local roots. Among Indian populations, U2 is the most ancient and widely spread subclade. In Tamil Nadu and South India, haplogroup U is present but in lower proportions compared to haplogroup M, which dominates Dravidian populations.

The Rakhigarhi DNA Study and Haplogroup U

One of the most significant findings regarding Haplogroup U came from the Rakhigarhi ancient DNA study. The Rakhigarhi female skeleton was identified as belonging to haplogroup U2b, confirming that U was present in the Indus Valley Civilization. This supports the idea that haplogroup U existed in India long before Indo-Aryan migrations, linking it to the ancestral South Asian populations. Some modern Tamil and South Indian populations still carry U2 subclades, showing continuity between ancient and present-day Dravidian maternal lineages.

Indo-Aryan vs. Dravidian Distribution of Haplogroup U

Haplogroup U is found in both North and South India, but different subclades are more common in each region. U2 is widespread in both Indo-Aryan and Dravidian-speaking groups, suggesting an ancient South Asian origin. 7 is more frequently found in Iran and North India, indicating some level of migration from the Iranian Plateau into India. In Tamil Nadu, U2 is present, but the dominant haplogroup remains M, which is a strong marker of Dravidian ancestry.

Haplogroup U and Maternal Lineage in South India

Haplogroup U2 is often found among tribal and caste populations in South India, indicating that it has been part of the genetic landscape for thousands of years. Even though U is less common than M in Tamil Nadu, its presence suggests that some maternal lineages in Tamil populations trace back to the Indus Valley Civilization and earlier South Asian hunter-gatherers. Unlike the Y-chromosome (which shows more Indo-Aryan influence in the North), mitochondrial DNA suggests strong maternal lineage continuity in South India.

The Significance of Haplogroup U in Tamil and Indian Ancestry

- Haplogroup U is an ancient maternal lineage found in both North and South India.

- U2, a major subclade of U, was present in the Indus Valley Civilization and continues to be found in Tamil Nadu.

- The Rakhigarhi study confirmed that a woman from the Indus Valley Civilization carried U2b, linking this haplogroup to South Asian ancestry.

- In Tamil Nadu, haplogroup U coexists with M but is found in lower proportions.

- This suggests that while South Indian maternal lineages have remained stable, there has been some genetic continuity with ancient populations from the Indus Valley Civilization and earlier hunter-gatherers.

Professor Raj Mutharasan’s discussion on Haplogroup U highlighted its deep history in South Asia, its presence in the Indus Valley Civilization, and its role in shaping the maternal ancestry of Tamil and Indian populations. While haplogroup M dominates in Tamil Nadu, the presence of U2 in some Dravidian groups reinforces the idea of genetic continuity from ancient times.

Professor Raj Mutharasan explained that Dravidian ancestry is not confined to Tamil Nadu but extends across various regions in India, including Kerala, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Maharashtra, Odisha, Chhattisgarh, and even parts of Central and Eastern India. Genetic studies indicate that Dravidian-speaking populations once covered a much larger geographical area, before the expansion of Indo-Aryan speakers. Haplogroups such as L, H, and R2—which are commonly associated with Dravidian populations—are found not only in Tamil Nadu but also in tribal and rural communities across South and Central India. Studies on mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) also confirm that maternal lineages in these states share deep-rooted connections with ancient South Asian hunter-gatherers and early agriculturalists, indicating a long-standing Dravidian presence before later Indo-Aryan influences.

Ancient Iranian Hunter-Gatherers and Their Connection to Indian and Tamil Ancestry

Ancient Iranian Hunter-Gatherers were a population that lived in the Iranian Plateau and surrounding regions around 10,000–12,000 years ago. They were distinct from Iranian farmers, who emerged later. Genetic studies show that these hunter-gatherers contributed significantly to the ancestry of the Indus Valley Civilization (IVC) people and later South Asian populations, including Dravidian-speaking groups in Tamil Nadu.

The Rakhigarhi ancient DNA study revealed that the genetic makeup of the Indus Valley Civilization people was a mixture of South Asian hunter-gatherers and Ancient Iranian hunter-gatherers, but without significant input from Iranian farmers. This finding disproved earlier theories that agriculture in India was introduced by Iranian farmers—instead, it suggests that farming practices in the Indus Valley developed independently. The genetic influence of these Ancient Iranian hunter-gatherers is still visible in some South Asian populations today, including in Dravidian-speaking groups, although Tamil Nadu’s genetic structure remains predominantly South Asian indigenous with minimal external influence.

In states like Maharashtra, Gujarat, and Madhya Pradesh, traces of Dravidian ancestry are present among tribal groups such as the Gonds, Bhils, and Kurukhs, whose genetic markers show similarities to South Indian populations. Linguistic and archaeological evidence further supports this, with remnants of Dravidian languages found in the Harappan Civilization and isolated tribal languages in Central India. The genetic continuity among Adivasi (indigenous) communities and Dravidian-speaking groups suggests that Dravidian ancestry played a significant role in shaping India’s early population structure. While Indo-Aryan migrations introduced new cultural and linguistic elements to North India, the genetic evidence confirms that Dravidian ancestry remains deeply embedded across multiple Indian states, reinforcing the idea that these populations represent some of the oldest continuous lineages in the subcontinent.

Key Takeaways from Raj Mutharasan’s Talk on Indian and Tamil Ancestry Through Genetics

- Dravidian ancestry predates Indo-Aryan migration, with genetic roots tracing back to early South Asian hunter-gatherers and Indus Valley Civilization inhabitants.

- Indus Valley Civilization (IVC) people were genetically linked to Dravidians, and their migration into South India contributed to Tamil ancestry.

- The Indo-Aryan migration (around 2000 BCE) brought haplogroup R1a to North India, but its influence in Tamil Nadu and South India was minimal.

- Tamil populations mainly carry haplogroups L, H, and R2, indicating a strong indigenous genetic lineage.

- Haplogroup U2b was identified in a Rakhigarhi skeleton, linking the maternal ancestry of Indus Valley people with modern South Asians, including Tamils.

- Mitochondrial haplogroup M is dominant in Tamil Nadu, showing strong maternal lineage continuity from ancient times.

- The Indo-Aryan migration route was traced through Central Asia into the Indus Valley via the Hindu Kush, contrary to earlier theories of direct migration from Iran.

- Language and genetics do not always correlate—many populations adopted Indo-Aryan languages despite having Dravidian genetic ancestry.

- Early Indians and Andamanese tribes share genetic similarities, particularly through haplogroup M, suggesting an ancient common ancestry.

- Tamil Nadu’s genetic diversity is shaped by early South Asian populations, with minimal external genetic influence from later Indo-Aryan migrations.

- Indus Valley people were not influenced by Iranian farmers, but rather developed agriculture independently in South Asia.

- Tribal populations in India, such as the Gonds and Kurukhs, retain genetic markers linked to ancient Dravidian ancestry, indicating a widespread early presence.

- The Indus Valley script and Dravidian languages may share a historical connection, though this remains a topic of ongoing research.

- The lack of ancient DNA samples from India limits a complete understanding of South Asian genetics, but available data strongly supports Dravidian continuity.

- Genetic studies show that the caste system influenced sampling biases, leading to misleading conclusions in some early genetic research.

- South Indian populations show strong genetic continuity, meaning the Tamil gene pool has remained largely stable for thousands of years.

- Maternal genetic lineage in India is far more uniform than paternal lineage, suggesting women from indigenous groups continued to pass on ancestry while male migration patterns varied.

- Indus Valley Civilization people had diverse facial features, with sculptures showing a mix of negroid, Alpine, and South Asian traits.

- Genetics confirms that the Indo-Aryans did not establish civilization in India but rather integrated into existing cultures, particularly in the North.

- Tamil heritage and ancestry are among the most well-preserved in India, with clear links to pre-Indo-Aryan populations and the Indus Valley Civilization.