Legacy of Danish Tranquebar

The Evolution of Tranquebar as a Trading Hub (1640-1730)

“It was a great humiliation to our proud nation that the same fortress should be at risk of falling, even as our most gracious king maintains a stronghold beyond India.” — Willum Leyel, 1644

Once a strategic Danish outpost, Tranquebar (Tharangambadi) evolved into a thriving European trading hub on the Coromandel Coast. The Danish East India Company, driven by its ambition to tap into the lucrative Indo-European trade, actively encouraged merchant activity in the settlement.

How Tranquebar Became a Trading Powerhouse

The Portuguese-Dutch conflicts of the 1640s unexpectedly benefited the Danes, as Portuguese traders sought refuge in Tranquebar, boosting revenues.

Governor Willum Leyel (1644) granted the Portuguese permission to build a Catholic church, further diversifying the town’s cultural fabric.

Danish-Indian Interactions flourished—by 1644, most Danish men stationed at Fort Dansborg had married local women, integrating into the community.

Military & Urban Expansion: Fort Dansborg’s dominance declined as Kongensgade (King’s Street) became the new commercial heart, lined with warehouses and European residences.

Tranquebar’s transformation from a military outpost to a bustling trading settlement is a testament to its strategic significance in global maritime trade. Today, its colonial legacy, Indo-European heritage, and architectural remnants stand as a reminder of its rich past.

Tranquebar and the Unyielding Bay of Bengal: A Battle Against Time and Tide

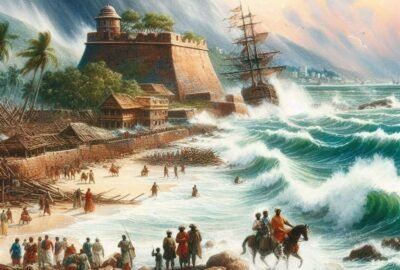

The 17th and 18th centuries were a time of great ambition and uncertainty for Tranquebar (Tharangambadi), the Danish trading post on the Coromandel Coast. But its greatest adversary was not rival European powers—it was the Bay of Bengal itself.

A 1671 map of Tranquebar shows no seawall along the beach. This wasn’t an oversight, but an acknowledgment of the futility of resisting the ocean’s might. By the 1690s, a seawall was built, yet the Bay remained untamed. The most devastating blow came on November 10, 1715, when a powerful storm raged from 1 AM to 7 AM, with violent winds from the south. The seawall collapsed, 40 cabins were washed away, and water surged over the fortifications, nearly engulfing Fort Dansborg. The governor, in his desperate report to Copenhagen, attributed their survival to divine intervention.

In the wake of this disaster, Tranquebar was left vulnerable. Bastion Prins Carl was hastily restored, but the rest of the seafront was reduced to a simple palisade. The missionaries, who were in the process of planning the New Jerusalem Church, reconsidered its location. Should they move it inland? Ultimately, advice from the Missionskollegiet in Copenhagen led to its construction within the town walls, where it still stands today.

The Danish East India Company, facing continued coastal erosion, even debated abandoning Tranquebar in 1727—considering either moving the town inland or relocating operations to Porto Novo. However, erosion appeared to stabilize in the 1720s, and Tranquebar remained where it was.

Today, the Bay of Bengal continues to challenge Tranquebar, with rising sea levels and increasing coastal erosion. The same questions that plagued its 18th-century residents remain relevant: How do we protect our coastal heritage?

The Indians of Tranquebar: A Glimpse into the 18th-Century Society

In 1790, 94% of Tranquebar’s population was Indian. The town’s diverse community included Muslims, dubashes (middlemen), artisans, and traders, each playing a crucial role in its socio-economic fabric. Among the 585 Muslims in Tranquebar, many were tailors, while the Ashes, who served as administrators for the Europeans, formed the second-largest group. Meanwhile, the sellings (cargo boat owners) and pintadores (painters) saw a decline over the years, reflecting the shifting dynamics under Danish rule.

The Danes deeply influenced local society, favoring certain castes and shaping social mobility. Lower-ranking castes often aligned with Danish authorities, sometimes challenging traditional hierarchies. Disputes over caste privileges, like the famous 1787-88 controversy involving the wealthy dubash Suppremania Setty, illustrate how colonial rule altered local power structures.

Interestingly, early Danish records from 1623-24 praised Indian masons as being more skilled than their European counterparts. Despite their reliance on Indian expertise, the Danes maintained strict policies on cultural interactions, including discouraging mixed marriages. The town also had a darker side—slavery was prevalent, with 4% of the population recorded as house slaves, owned by both Danes and affluent Indian families.

Protestant missionaries in Tranquebar played a unique role, blending religious outreach with architecture. Their New Jerusalem Church (1717-18) reflected Indian influences and caste-based divisions, contrasting with the European-style Zion Church. However, by the late 18th century, missionary enthusiasm waned, leading to the formal closure of the mission in 1825.

Today, Tranquebar’s layered history—of trade, caste struggles, colonial rule, and missionary influence—offers a fascinating lens into India’s past. Its legacy continues, with a small Protestant community still present, echoing the town’s vibrant historical narrative.

Tranquebar’s Fortifications and the Struggles of Danish Officials (1730-1800)

Tranquebar, a small Danish colony on the Coromandel Coast, faced relentless challenges—not from invading armies, but from nature itself. Coastal erosion, shifting sands, and the corrosive salt-laden air made defense a constant struggle. By 1730, the eastern sea walls had to be replaced with wooden palisades, offering little military value. Cannons rusted rapidly, and monsoon winds filled the moats with sand, requiring frequent clearance.

When Haidar Ali’s forces approached in 1781, desperate last-minute fortifications—including a moat and reinforced palisades—proved inadequate. Only a hefty payment of 28,000 silver coins prevented an attack. Despite later modernization efforts, Tranquebar’s strategic importance waned by the early 19th century.

Danish officials in Tranquebar also faced hardships. With modest salaries, many officers struggled to maintain a respectable lifestyle. Civil servants could supplement their income through trade, but military officers had fewer options—except for engineers, who profited from supplying building materials. Some resorted to running small inns, while others, facing financial strain, turned to excessive drinking, weakening discipline in the garrison.

Yet, among them were dedicated individuals who left a mark. Lieutenant Colonel Mathias Mühldorff played a crucial role in fortification upgrades. First Lieutenant Claus Kröckel, an architect and building inspector, contributed to significant structures like the New Jerusalem Church.

Building a Colony: Tranquebar’s Public Works and Military Infrastructure (1795)

By the late 18th century, Tranquebar underwent significant urban and military transformations. In 1795, a former residence on Prins Christiansgade was converted into barracks for 28 soldiers, replacing their previous, less-than-ideal lodging in stables on Parade Square. Officials noted that these old quarters were inappropriate for public settings, as soldiers often remained unclothed while in barracks. Once the troops relocated, the stables were demolished to make way for a new residence for the regimental field cutter.

These developments reflected broader colonial ambitions—blending European architectural styles with strategic urban planning. Tranquebar’s evolution highlights the intricate relationship between military necessity, public works, and governance in colonial settlements.

History teaches us that infrastructure is more than just buildings—it shapes societies, enforces order, and reflects the aspirations of those who build them.Tranquebar’s story is a reminder that colonial ambitions often clashed with harsh realities. Military strength alone was never enough—adaptability, resilience, and resourcefulness defined survival.

Tranquebar: A Forgotten Danish Colony (1800-1845)

Once a thriving Danish trading post, Tranquebar (Tharangambadi) saw its fortunes decline between 1800 and 1845. With trade collapsing and British dominance in South India growing, the settlement became a financial burden for the Danish Crown.

The Asiatic Company’s withdrawal in 1796 marked the beginning of the decline. Danish authorities attempted to expand their territory, even mortgaging villages to the Raja of Tanjavur, but British intervention thwarted these ambitions. By the early 19th century, the town was in a state of economic stagnation, struggling under heavy British tariffs that crushed any hopes of revival.

Danish governance introduced reforms to retain control, such as offering Danish citizenship to foreign homeowners and regulating property modifications, but these measures did little to stop the decay. Tranquebar’s fortifications crumbled, and by 1801, when British forces occupied the town, its defenses were so weak that surrender was immediate and without resistance.

By 1834, Tranquebar had become a ghost town. The European quarter emptied, streets fell silent, and abandoned houses stood as relics of a lost era. Danish missionary David Rosen described a settlement devoid of trade, where most European residents were pensioners and widows seeking an inexpensive retirement. The Indian community also shrank, with entire trades disappearing and once-distinct Indo-Portuguese families fading into history.

Today, the remnants of Danish Tranquebar stand as a testament to its forgotten past—a coastal town that once thrived on commerce, now remembered through its fading colonial architecture and silent streets.

What are your thoughts on preserving historic coastal settlements in the face of climate change? Let’s discuss!

#Tharangambadi #Tranquebar #Heritage #MaritimeTrade #ColonialHistory #Architecture #DanishIndia #SouthIndia