கோவில் திருக்குளங்களை பராமரித்த சோழ நாட்டு வணிகர்களான கவறை செட்டிகள்

சோழ நாட்டில் திருவாரூரில் பிறந்த தண்டியடிகள் நாயனார் என்பவர் பிறவியில் பார்வையற்றவர். கோவில் திருக்குளத்தில் இறங்கி மண்ணை (குளங்கல்ல) வெட்டியெடுத்துக் குளக்கரையில் இருந்து ஒரு கயிற்றை கட்டி அதைத் தடவிக் கொண்டே கரையிலே போடுவார். இறுதியில் தான் குளங்கல்லிய (தூர்வாரிய) குளத்தில் மூழ்கி எழுந்து இறைவன் அருளால் கண் பார்வை பெற்றார்.

சோழ தேசத்தில் திருவிடைமருதூர் கோவிலில் பத்தாம் நூற்றாண்டைச் சேர்ந்த கல்வெட்டில், அரசரின் பெயர் கிடைக்கவில்லை. கோவிலுக்கு ஆடல் விடங்கர் என்ற நடராஜப் பெருமானின் செப்புத் திருமேனிக்கு ஆபாரம் செய்து கொடுத்த, ஸ்ரீ காரியம் என்ற பதவி உடைய (இராஜாங்க பணி) இங்கணாட்டு பல்லவ அரையர் பற்றிய தகவலும் கிடைக்கின்றது.

முன்பு ஒரு காலத்தில் அந்த கோவில் பண்டாரத்திற்கு கவறை செட்டி ஒருவர் அளித்த பொன்னையும், திரைமூரைச் சேர்ந்த 300 ஊர் சபையோரும் (பிராமணரும்?), 400 நகரத்தாரும் இணைந்து பொன் மாலையை ஆடல் விடங்கர் என்ற நடராஜருக்கு அளித்துள்ளனர். இந்த மாலை எழுநூற்றுவன் எனப் பெயரிடப்பட்டுள்ளது. எனவே எழுநூற்றுவர் என்போர், ஊர் சபையோரும், நகரத்தாரும் சேர்ந்த குழுவினர் என்பதை அறியமுடிகிறது.

இதே கல்வெட்டில் குளங்கல்ல (குளம் தூர்வார) பொன் அளித்த வணிகர் பற்றிய குறிப்பு வருகின்றது. இவர் மாசாத்தன் ஊரைச் (மாசாத்தநூர்) சேர்ந்த “திருப்பாதாள கவறை செட்டி திருநாவுக்கறையன்” எனப் பெயர் வருகின்றது. திருநாவுக்கரசர் என்ற பெயருடன் பொருத்திப் பார்க்க.

இவர் குளம் தூர்வாரும் பணி செய்வதற்கு என்றே, கோவில் திருப்பண்டாரத்தில் பொறக் காசுகளை வைப்பாக வைத்துள்ளார். அதில் வரும் வட்டி வருமானம் கொண்டு கோவில் குளங்கள் சீரமைக்கப்பட்டன. தமிழகத்தின் பல கல்வெட்டுகளில் வணிகர்கள் கோவில் குளம் அமைப்பது, சீர் செய்வது பற்றிய செய்திகள் நமக்கு கிடைக்கின்றன. தமக்கு வரும் வருமனத்தில் நீர் நிலைகள் அமைப்பது அவர்கள் அறமாகக் கருதியுள்ளனர்.

மேலும், வணிகம் பொருட்டு செயல்படும் வணிகக் குழுக்கள் ஊர்களில் தங்காது தனியே தாவளம் அமைத்து தங்குவர். அவ்வாறு இருக்கும் போது, வணிகம் பொருட்டு எங்கெல்லாம் இவர்கள் பயணிப்பார்களோ அங்கெல்லாம் நீர்நிலைகளை, வாவிகளை, கிணறுகளை ஏற்படுத்தும் வழக்கத்தைக் கொண்டுள்ளனர்

மேலும், ஐநூற்றுவ வளஞ்சியர் பிரிவைச் சேர்ந்த கவறைகள் செட்டிகள் என்றே சோழர் காலத்தில் அழைக்கப்பட்டுள்ளனர். இவர்கள் தங்கிய ஊர் மாசாத்தநூர் என மாசாத்தனோடு தொடர்புடையது. மாசாத்துவான் என்போர் சங்க இலக்கியத்தில், வணிகம் பொருட்டு, சரக்குகளை கள்வர்கள் கவராமல் காவலர் துணைக் கொண்டு எடுத்துச் செல்லும் ஏற்றுமதி இறக்குமதி வணிகக் குழு வாகும். இதனையே இவர்கள் கடல் வணிகத்தில் செய்தால் மானாய்க்கன் எனப்படுவர்.

தென்னக கல்வெட்டுகளில் ஒரே குடும்பத்தைச் சேர்ந்த தந்தை மானாய்ககனாகவும், மகன் மாசாத்துவானகவும் இருந்துள்ளனர். தரைவழியில்யில் வந்த பொருளை கடலின் வழியில் அனுப்பி வைக்கும் வணிகத் தொழியில் செய்த இவர்கள் வணிகம், போர்ப்படை பயிற்சிக் கொண்ட குழுவினர். மேலும் மாசாத்துவானாக இருந்த ஒருவன், பின்னாளில் மானாய்க்கனாக மாற்றம் அடைந்துள்ளனர். இந்த தொழில் முறை சோழர் காலத்தில் “கடத்து வளஞ்சியம்” என அழைக்கப்பட்டது. இவ்வாறு வளஞ்சியம் செல்லும் போது கள்வர்களோடு சண்டையிட்ட இறந்த “வலங்கை உய்யகொண்டான் கவறை விடங்கன்” பற்றிய குறிப்புகள் கல்வெட்டுகளில் வருகின்றன. வணிகக் கல்வெட்டுகளில் கவரைகளுக்கும் எட்டி, சாத்தன் என்ற பெயர்களும் இடம் பெறுகின்றன. சங்க காலத்தில் சாத்து வணிகர்கள் செய்து வந்த ஏறு சாத்து, இறங்குச் சாத்து தொடர்ச்சியாக இவர்கள் செயல்பட்டிருக்க வாய்ப்புள்ளது.

தங்களது வருமானத்தில் ஒரு பகுதியை அறப்பணிகள் செய்ய என்றே தனியே கணக்கு எழுதி எடுத்து வைக்கும் மேலான வழக்கம் அனைத்து தமிழக வணிகர்களிடமும் இருந்துள்ளது. இந்த அறப் பண்பே வணிகத்தை தமிழகத்தில் மேன்மை அடையச் செய்துள்ளது.

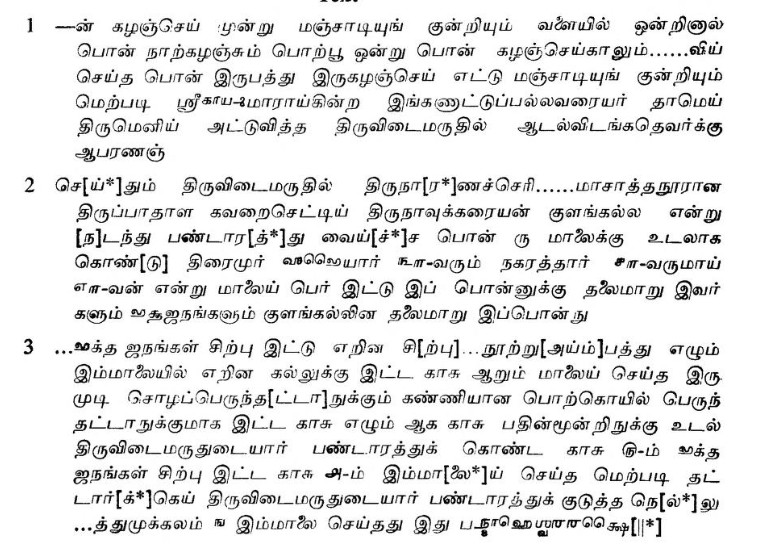

கல்வெட்டு:

“திருவிடைமருதில் திருநா[ர*]ணச்செரி…… மாசாத்தநூரான திருப்பாதாள கவறைசெட்டிய் திருநாவுக்கரையன் குளங்கல்ல [ந]டந்து பண்டார[த்*]து வைய்(ச்*]ச பொன் ”

South Indian Inscription Volume; 23

No. 212 (A. R. No. 222 0/1907.)

Tiruvidaimarudur, Kumbhakonam Taluk, Tanjavur District Mahalinagsvami temple—on the same wall

The historical inscription in question, which dates back to approximately the 10th century A.D., begins with a notable gap in its text, resulting in the loss of information regarding its origin and the specific king associated with it. Due to this missing portion, scholars are unable to definitively attribute the inscription to any particular ruler.

The primary focus of the inscription is the commemoration of an event involving the installation of an image of Nataraja, also known as Adalvidangadevar, within a temple. This significant act was undertaken by an individual named Sri Karyaim Inganattu-Pallavaraiyar. Apart from the establishment of the sacred image, Sri Karyaim Inganattu-Pallavaraiyar is credited with offering numerous gold ornaments to the deity, thereby contributing to the adornment and grandeur of the religious site.

Additionally, the inscription documents a monetary contribution made by a person identified as Kavarai Setti, who resides in the Tirunaranachcheri quarter. This financial support was originally intended for the excavation of a tank, a water reservoir that would serve the community. However, the inscription reveals a deviation from this initial purpose. Instead of using the funds for the construction of the tank, the Sabha of Tiraimur, a group comprising 300 members, along with the Nagarattar, consisting of 400 members, and other unnamed devotees, decided to channel the funds towards a different endeavor.

Surprisingly, the collective decision was to utilize the contributed amount to create a splendid golden necklace for the deity. This opulent piece of jewelry was named Elunurruvan, symbolizing the collaboration and dedication of both the Sabha of Tiraimur and the Nagarattar. Thus, the inscription not only records the religious event of installing the image of Nataraja but also sheds light on the generous contributions and intriguing decisions made by the individuals and groups involved in the temple affairs during that era.

In the same inscription, there is a mention of a merchant named “Thirupatala Kavarai Chetty Thirunavukkarayan” from Masathan Ur (Maasaathanur), who generously contributed gold to repairing the Temple Pond (Kulangalla).

Thirunavukkarayan has notably deposited gold coins in the temple Tirupandaram, specifically earmarked for the excavation of a pond. Numerous inscriptions across Tamil Nadu shed light on the commendable practice of merchants and traders endowing temple ponds, deeming it virtuous to construct water tanks from their earnings.

Furthermore, it is observed that business communities engaged in commerce, rather than residing in urban centers, often opt for solitary habitation. Their inclination towards constructing water bodies, ponds, and wells persists wherever their trade endeavors take them.

During the Chola period, the Kavarai affiliated with the Ainutuva Valanjiyar sect were referred to as Chettis. The settlement associated with their residence, Masaththaanur, is linked to Maasaathuvan. In Sangam literature, Maasaathuvandenotes an export-import trade group conducting business without the aid of guards for Caravans of trade purposes. In maritime trade, they are designated as Maanaaikkan, with the father being known as Maanaaikaka and the son as Maasaathuvan. This group, proficient in both business and military aspects, managed the transportation of goods by land and sea. The transition from Masathuvan to Manaikakan reflects their evolution in this industry, recognized as valanjiyam during the Chola era.

Other Ainnotruvar Inscriptions mention of Uyyakondan Kavarai Vidangan, a deceased Kavarai who engaged in conflict with the Kalvars during a trade caravan journey. Trade inscriptions further reveal the names of Kavarai with titile Eti, and Satan, suggesting their involvement in a series of Eru Sathu (Export) and Irangu Sathu (Import), reminiscent of the practices of Sattu merchants during the Sangam period.